A sample of today’s headlines across global media platforms with the search word ‘elderly’ makes for sobering reading.

’92-year-old woman’s house ransacked in coronavirus scam.’

‘Thieves offering to shop for the elderly and then stealing from them.’

‘Can an app help fight loneliness in elderly people?’

‘Abuse taking place in 99% of care homes in England, survey shows.’

‘How about we invent things to make life easier for OAPs, not harder.’

‘Elderly UK patients denied resources as doctors forced to make ‘grave decisions.'

‘Coronavirus: What are the new rules on visiting aged residential care homes?’

‘Home intruder beaten by elderly female bodybuilder.’

‘Should older drivers be re-trained for modern roads?’

‘Japan wants to go cashless, but elderly aren’t so keen.’

‘Care home virus deaths ‘far higher’ than figures.’

‘How can cities be improved for older people?’

‘How should the government prepare for an ageing population?’

For various reasons, the elderly in our communities have become a focus of discussion at this time of pandemic. In countries overwhelmed with patients needing ICU care, the elderly have received low priority for treatment given their low probability of survival compared to younger and healthier infected patients. In countries such as New Zealand, where lockdown processes are in place, people aged over 70 are classed as vulnerable and advised to stay in their social isolation bubble. Elderly people who are dying, either in their homes or hospitals, are unable to be surrounded by their loved ones due to enforcement of the lockdown rules. The economic devastation of the pandemic will affect all people, including the elderly, with issues of reduced services being delivered by key businesses, rising unemployment, increased government debt, and currency and asset devaluation.

In forming a recovery response to the Covid-19 pandemic, global leaders in health, economics, politics and ethics are being faced with profoundly complex issues. This brief discussion considers the importance of flourishing in old age as a key to addressing some of these complexities.

Population demographics and changes have been a hot topic for expert discussion. In 1968 John Calhoun’s ‘Universe 25’ rodent experiment and Paul Ehrlich’s book ‘The Population Bomb’ both made frightening predictions for uncontrolled and unsustainable human population growth. Sarah Harper, in her book ‘How Population Change Will Transform Our World,’ describes the profound implications our planet faces from large-scale demographic shifts in populations. The Covid-19 pandemic has focussed some of these messages.

Policy makers all over the world have been aware of the risks of overpopulation and the resource limitations and social pressures which result from this. The concept of ‘replacement level’ describes the capacity of a country to maintain its population, and is primarily affected by fertility and birth rate, death rate, and immigration.

Two thirds of the world’s countries are near or below replacement level, and for many this transition has occurred rapidly and recently. Such demographic changes have significant impact across all aspects of human life, including economic, education, health, and welfare.

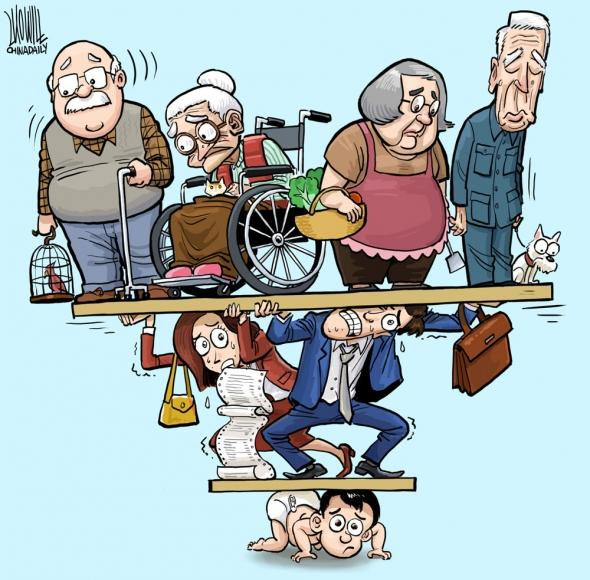

In high income countries, babies are born with the opportunity to live long, heathy lives. Women are reducing their childbearing rates. As a result, the population demographic is shifting to an ageing one. The relevance of this is in considering the bulges of different age groups in a society, and the impact of these on community function. The ‘Demographic Dividend’ describes the economic growth potential where the working age population is larger than the non-working-age portion. One of the limitations in this concept is defining what it means to be a contributor rather than a drain on society. Confining contribution to simply economic terms ignores the great resource of life experience, wisdom, child care support, and nurture that the ageing, non-working members of a society can offer.

However, the reality in most ageing societies, particularly those with frail elderly people, is that the Demographic Dividend is reversed; social resources are depleted by the cost of caring for this bulge in age group, and the relative reduction in financial contributors to the society. Population implosion rather than explosion is the new problem in ageing societies with shrinking workforces.

Some are calling the 21st century ‘The Century of the Centenarian’ given that recent research suggests over half of babies born now will live past 100 years of age. The Support Ratio (the number of people of a working age to those over that age) has seen a shift historically from five workers to the current two for every older person in high income countries. This decline in the Support Ratio increases pressure on all members of that society, and in particular the welfare supports, such as Old Age Pensions.

The concept of the pension system when introduced by Otto von Bismarck in Prussia 1881 was a radical departure from the expectation of working until one died. Bismarck’s proposal was that the state should care for those unable to work due to age or infirmity. The age for entitlement was 65 years of age, in a society where half the European population was dead by the age of 45. Extrapolating this, the pension eligibility in high income countries now would be 103. Currently, the life expectancy in high income countries is over 80 years, and the safety net concept of the pension developed by Bismarck now has become, for most, an expectation of state-funded leisure or non-working for the 15 or more years at the end of life. This becomes a social and economic challenge which is unsustainable when people are living longer, and the bulge of baby boomers are entering the old age demographic at the same time. Governments and policy makers will be forced to make morally difficult decisions about who to distribute resources to, with an increasing resource-consuming old age population and a diminishing income-producing one.

So what are some of the solutions to this moral challenge?

- Older people working longer.

- Increase population growth, whilst being mindful of the delay until children are contributing positively to the demographic dividend, as well as environmental pressure, and considering the role of immigration policy.

- Consider measures to move the frail aspect of the ageing population into the end of lives, to give opportunity for the otherwise functional elderly to contribute positively to society, and not be seen as a drain on resources.

- Programmes for better health

- Enhanced social connection and interdependence

- Employment opportunities

- Urban design and systems to facilitate ageing populations to participate and integrate.

The Ministry of Health in New Zealand updated its ‘Healthy Ageing Strategy’ document in 2019, with the vision that:

“Older people live well, age well and have a respectful end of life in age-friendly communities.”

The strategic themes of the document include words such as ‘prevention’, ‘resilience’, ‘rehabilitation’, ‘support’ and ‘respect’.

The Ministry of Health has also produced material accessible in written, audio and sign-language formats titled ‘Ageing well: How to be the best you can be.’ This provides helpful information on topics ranging from mobility and nutrition to sexual relations and keeping safe at home.

In addition, the World Health Organisation has recognised the global trend towards an ageing population, and produced a strategy document which highlights the need to invest in and build systems to meet the needs of these ageing populations.

The Life and Living in Advanced Age study performed in New Zealand included many of my patients, covered 937 people over the age of 80, and was the world’s first longitudinal study of an indigenous population aged over 80. The research team explored what it means to live successfully as an older person. The primary concern of people interviewed was not their own personal health. Rather, they worried about wellness in their friends and family, and their ability to maintain social connections, over their personal heath and financial issues.

The New Zealand environment sees an ageing workforce, with one in five people aged over 65 in paid employment, and this number is predicted to rise to one in three by 2051. A document from the Ministry of Social Development describes the potential for transformation in the working lives of older people and the capacity for this to solve workforce shortages.

The UN World Population Prospects reports that by 2050 those over 65 will outnumber those under 15 for the first time in world history, with 70% of the world’s population living in cities. This reality should drive policies to build city communities which are safe, connected and prosperous. Sion Jones in his co-chair role for Habitat III produced a report detailing ten critical areas for attention. These are:

- Build cities for all.

- Invest in sustainable transport.

- Create accessible green and public spaces.

- Foster intergenerational communities.

- Design housing for life.

- Recognise informal street-based livelihoods.

- Promote healthy urban environments.

- Combat air pollution.

- Plan for living with dementia.

- Strengthen disaster resilience and response.

Cities are responding to this challenge already, with the UK building ten new towns focussed on addressing these issues; Berlin attending to accessibility projects; Milan winning an award for building design and public transport initiatives for elderly; China and Malaysia encouraging architectural initiatives geared for elderly people.

Many of these initiatives are recognising the value of integration rather than segregation, where gated communities of exclusively elderly people as a lifestyle solution are actually cutting people off from the rest of society. And these integrated solutions, rather than being motivated by characterising ageing as a problem, promote the value of these strategies for the whole community.

I have book-ended this with a few more of the headlines I found on 20 April 2020 and which opened this article. They speak to a response for our ageing population which encourages flourishing as a goal.

‘US woman celebrates 103rd birthday by volunteering.’

’94-year-old ‘wonder woman’ makes full recovery from COVID-19.’

‘New high-tech living transforming the lives of retirees.’

‘The older Aussies leaving retirement for work – and loving it.’

‘Grandmother shows how to keep fit during lockdown.’

‘Coronavirus: Captain Tom Moore passes 23m in NHS fundraising.’

‘How can older people play a bigger role in society?’